The Changing Face of Portraiture

/ Royal Society of Portrait Painters

Chronicles on Canvas by Anna Godfrey

It is the expression of the young woman that we notice first. The corners of her lips upturn in a knowing way, as if the two of you are silently acknowledging a long-standing joke. She looks directly out, her pale face shining against the lustrous black of her cap. Within a moment of noticing her gentle expression, our eyes are drawn down to her hands which, unlike her face, appear restless – twisting a pair of expensive buff leather gloves. The single red ring on her wedding finger gives a clue to her identity: this is Christina of Denmark, a sixteen-year-old widow. We are seeing her captured in a full-length portrait by Hans Holbein in 1538, commissioned by none other than King Henry VIII.

This striking painting of the teenage widow is one of the National Gallery’s most renowned artworks. Christina’s youth is at odds with the heavy black garments which signify her widowed status, and yet it is exactly this contrast that accentuates her beauty. Her hands appear more elegant against the heavy, puffed sleeves; her bright expression highlighted by her sombre garments. The teal background is stripped of embellishment, lustrous only in the strength of its colour. The way in which the girl’s shadow – and, to the right, possibly the shadow of an open door – falls upon the teal creates a sense of illusionistic space which is compelling even to a contemporary viewer. Although Henry VIII would go on to marry Anne of Cleves in January 1540, upon seeing Holbein’s painting of Christina he is said to have ordered music to be played all day and the portrait would, unusually, remain in the King’s possession for the remainder of his life.

To today’s viewers, the artwork symbolises a sliding door: a young woman who unknowingly dodged a likely ill-fated union. The success of this painting resides not only in the confidence of its composition and the sensitivity with which Holbein has rendered Christina’s presence, but also the fascinating historical chapter it conveys.

'Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan' epitomises much of the motivation behind historical portraiture. The artwork was commissioned by a ruler to depict a person of high status. The painting’s composition – full-length at King Henry’s request to see the entirety of his potential wife – is influenced by the commissioner’s preferences and, perhaps the hardest objective to pin down, the artist was challenged with balancing a lifelike rendering (the twitching fingers caught mid-movement, the beginnings of a smile) with a subtly exaggerated state of grace. This was an artwork asked for by a king, of a person of great social standing, in order to accentuate the virtues valued in the sitter. In this case: youth, wealth and beauty. By and large, historically commissioned portraiture has been somewhat constricted by this push and pull of expectation as it was predominantly aristocracy who possessed the money, time and connections to support it. Such patronage engendered works that would become cornerstones of the art historical canon – Van Eyck’s 'Arnolfini Portrait' (1434), Leonardo’s 'Mona Lisa' (about 1503–6), Klimt’s 'Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I' (1903–7) – but what adjustments the artist may have made to meet the patron’s expectations is not always clear.

Today, however, the definitions of both who is able to commission a portrait and who is worthy of being portrayed have greatly expanded. Although portraits are still commissioned by institutions to commemorate individuals whose work has impacted society in a significant way, access to painters is no longer reserved for the few and organising societies are publicly available to match artists with interested individuals. With this increase in accessibility comes an enriching of both subjects and styles.

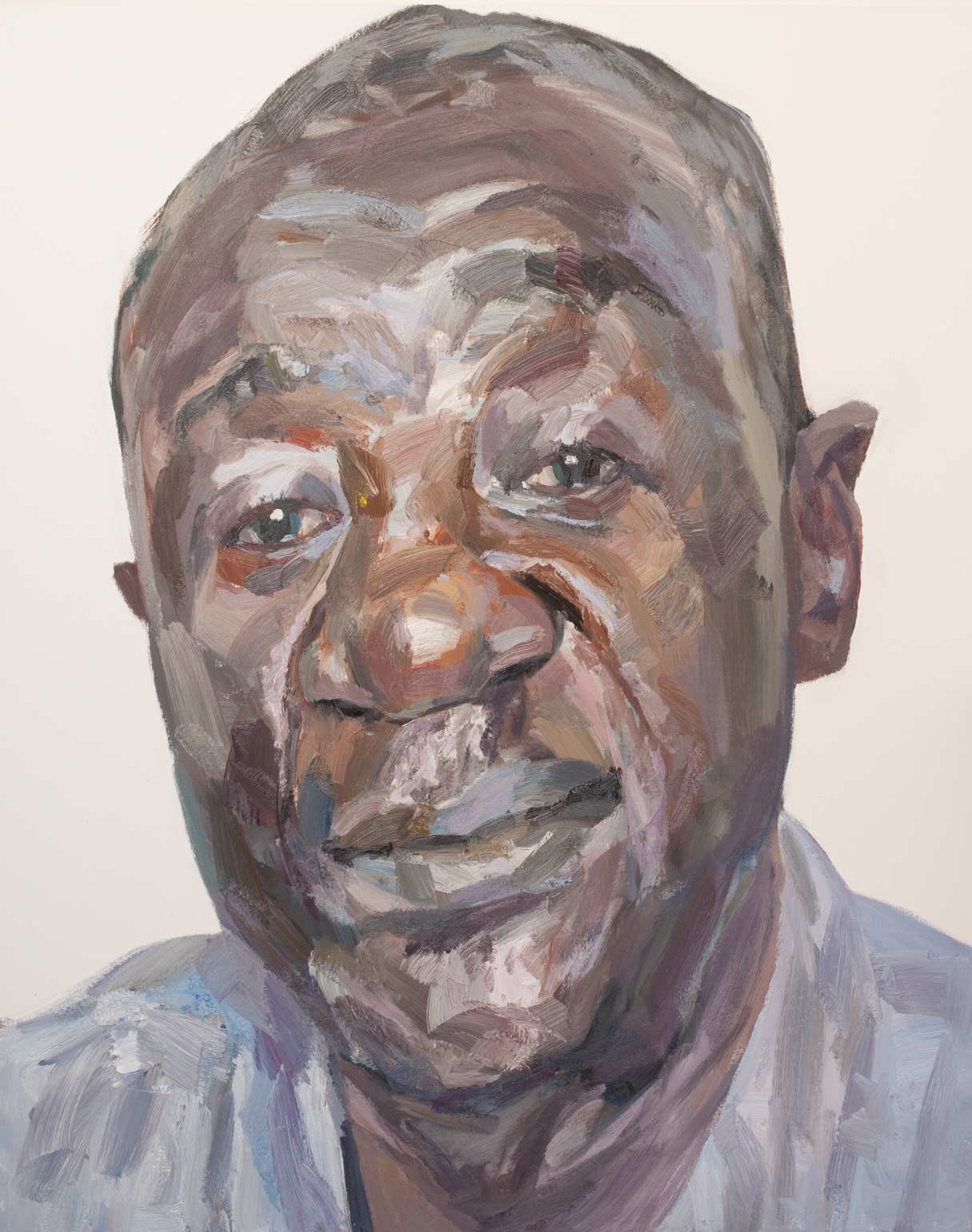

Tim Benson is one such artist working today to challenge the conventions of the traditional portrait. Benson is an oil painter whose work is characterised by tightly cropped compositions in which the sitter’s head almost touches the edge of the canvas. He applies patches of paint in thick impasto, working with a focused selection of six colours and tending to use only one large brush for each painting. Such self-imposed limitations create a recognisable style in which robust forms are built with confident, visible brushstrokes. His 'Portrait of a Man' (2023) bears similarities to Lucian Freud’s 'Frank Auerbach' (1975–6): a man’s head tilted down in emphasis of the sitter’s forehead, upon which light interacts with bumps and hollows to almost sculptural ends. Speaking about his technique, Benson is clear about the physicality of the application: ‘I need to have a bit of anger in me to paint’. This emotion is apparent in his work, in which paint is struck against the canvas and blending is rare. The medium is made explicit. The result is a patchwork of heavy dabs of colour in which each broad mark signals a point of light or shadow. These jostle alongside one another in a style reminiscent of confronting portraits such as Rembrandt’s 'Self-Portrait as Zeuxis Laughing' (about 1662) or, among Benson’s contemporaries, Jenny Saville’s 'Stare' (2004–5).

Benson’s demand for honesty from his materials is indicative of his overall approach. When we discuss the differences between famous historical portrait commissions and his own work, he is direct in seeking to set himself apart: ‘It’s [portraiture] been used as a sort of a tool for making people look pretty. That’s definitely not what I’m interested in [...] I’m not in the business of flattery.’ Instead, Benson sees his role as that of storyteller: ‘It’s a chronicle of somebody’s existence, I suppose, in a two-dimensional image.’ This desire to tell the story of an interesting life has led him to commissions depicting people with facial difference, such as the British actor Adam Pearson who has neurofibromatosis. Benson describes the aim of this piece as ‘celebrating the humanity of the individual rather than, you know, something that’s just skin deep’. It is the faces which tell the most unusual stories which captivate the artist and enable him to ‘challenge the conceptions of what is traditional beauty and what is the reality of beauty.’

At times, the stories Benson seeks take him further afield. He has collaborated with charities and NGOs to ‘paint portraits of people that they work with, building awareness.’ In 2016, he worked with King’s Sierra Leone Partnership to produce 40 portraits of individuals on the frontline of Sierra Leone’s Ebola epidemic. The resulting large-scale paintings show Sierra Leonean nurses, doctors, security personnel and screeners. The relaxed, often-smiling faces are presented on white backgrounds, stripped of the context of the hospital wards, protective clothing or the medical equipment surrounding the sitters when Benson met them. This approach differs to the usual atmospheric backgrounds of his pieces, a decision informed by the artist’s attempt to divorce the sitter from their medical setting and the stigma this carried. ‘Trying to make people aware of the psychological side of the epidemic.’ In this way, Benson describes his art as carrying a social mission: ‘almost like being a journalist, there’s a sort of documentary way of working’.

This journalistic tact isn’t without precedent. War artists such as Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson and Stanley Spencer produced work that not only captured scenes of conflict but communicated the psychological and emotional trauma of combat. The value of their pictures lies not only in being records of warfare, but in conveying what it feels like to experience it. One such artist is Henry Tonks, the British surgeon turned figurative painter who worked as a war artist during World War I. Particularly relevant to Benson’s art are Tonks’s pastel portraits of wounded soldiers, produced prior to facial reconstruction treatment at military hospitals in Aldershot and Sidcup. Not only are the portraits powerful in their unflinching depictions, but they are made – as Benson points out – ‘with a sort of compassion and sensitivity’ devoid of voyeurism. Benson works hard to bring such respect to his own practice, ‘to tell the stories of the people, not just the condition or the situation.’

The question of whether artists – including filmmakers, actors and authors – have a responsibility to engage with current political issues or to depict historically marginalised communities, and the sensitivities of going about this, has increasingly come to the fore in recent years. Portraiture, it could be argued, carries a unique responsibility within this conversation: not only as taking a single sitter as focus but also as a format ripe for modernisation.

Public sculpture commissions such as the Fourth Plinth’s 'Alison Lapper Pregnant' by Marc Quinn (2005), 'Antelope' by Samson Kambalu (2023) and, today, Teresa Margolles’s 'Mil Veces un Instante (A thousand times an Instant)' are prime examples of the prestigious role of the commission and its important placement – in Trafalgar Square – attracting ideas that question the traditional monument. The long-standing history of the painted portrait creates a similar playground for subversion. In many ways, the commissioned portrait appears bound by the assumptions of its historic function: as an elevation of an individual, a spotlight reserved for society’s elite. If centuries of art history have fortified this framework, in what new and interesting ways might today’s painters disassemble these assumptions to create imaginative results? Tim Benson’s incisive approach to his commissions and his impassioned view of the power of art to benefit society is one answer, but there are countless artistic responses awaiting discovery within the varied range of RP Painters.

List of Images

1. Mark Sepple, Tim Benson & Adam Pearson

2. Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497/8 - 1543, 'Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan', 1538, Oil on wood, 179.1 x 82.6 cm. Presented by the Art Fund with aid of an anonymous donation, 1909 © The National Gallery, London

3. Tim Benson NEAC FROI RP, 'Adam Pearson'

4. Rembrandt, 'Self-portrait as Zeuxis Laughing'. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

5. Tim Benson NEAC FROI RP, 'Mohammed, Ebola Survivor, Freetown, Sierra Leone', 2015

Contact Us for a Portrait Commission

Martina Merelli, Fine Art Commissions Manager

+44 207 968 0963