The Changing Face of Portraiture

/ Royal Society of Portrait Painters

Layers of Looking by Anna Godfrey

In Scottish artist David Caldwell’s full-length portrait 'Girl with Orange Jumper', the sitter relaxes on a padded chair placed on a low wooden platform. An otherwise muted colour palette of concrete wall, black platform and gunmetal-grey chair is punctured by a bright orange jumper which draws us, like a bull’s eye, towards the woman. Her expression appears engaged, as if listening to someone behind the viewer finishing their point. A natural light falls on the right side of her face, throwing a soft shadow against the plain background. There is a sense of a single moment being suspended and, yet, scattered beneath her chair are tape markings – residues of repetition. Signs of the chair being adjusted and marked, perhaps over the course of several sittings. Although the orange jumper holds centre stage, it is a sense of time which holds the piece together. As David says when we speak on the phone, ‘a good portrait is layers of looking […] the light, the external conditions…people move. There’s a sort of distillation process going on.’

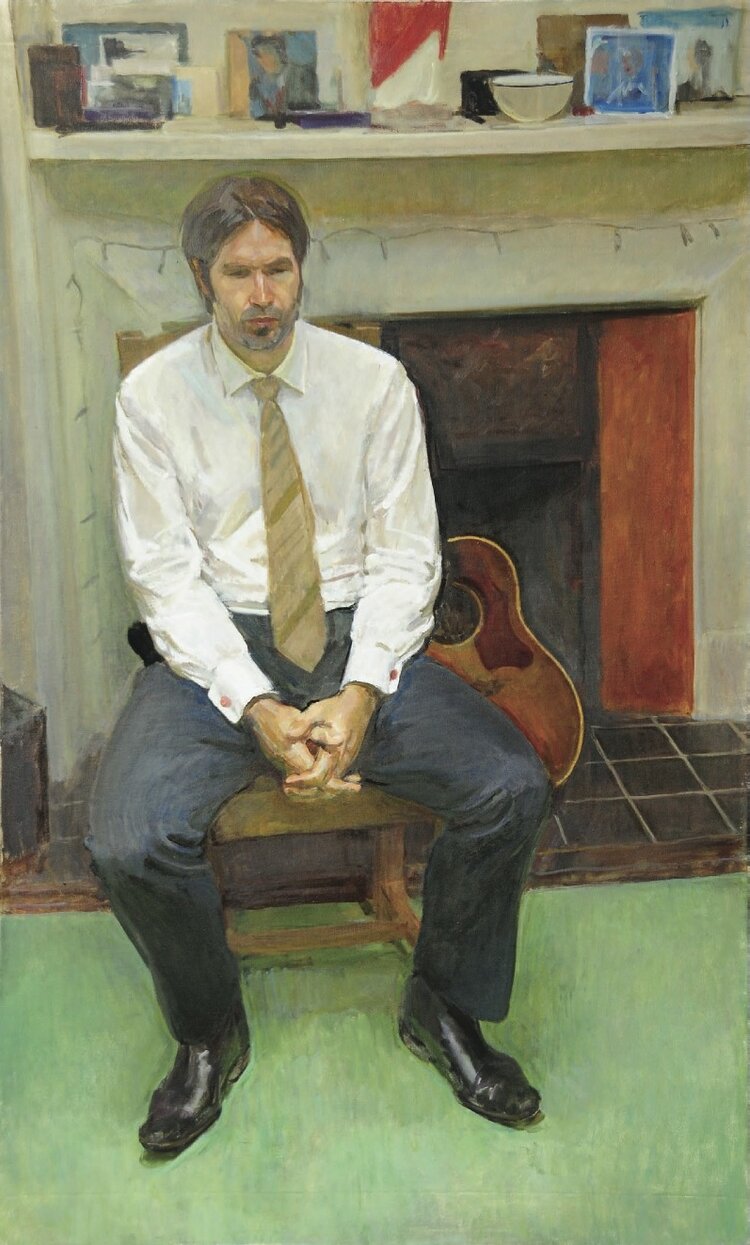

Pace and patience are crucial to David’s considered process. This is apparent when looking through his portraits which, though diverse in composition, consistently retain a pensive, reflective quality. His sitters are often depicted as if lost in thought; their faces rest in natural expressions, seemingly unaware that they are being painted. The scope and complexity of the compositions vary. Some, including 'Portrait of Justin Currie', portray a sitter full-length, situated within a homely room surrounded by clusters of familiar objects. Others, such as the tender 'Vanessa', take us within inches of the subject’s face. Here the background is reduced to rough brushstrokes, our attention beckoned by careful details like the white light that outlines the scooping hollow behind Vanessa’s collarbone. Though ranging in proximity, angle and intricacy of scene, the consistent result of David’s portraits is an unassuming sense of intimacy.

A feeling of connection is central to any portrait process, reflective of the trust which develops between the artist and their subject: ‘Hopefully they really like your work and they’re happy for you to make the decisions.’ David notes that it’s natural for some hesitancy to be present in the beginning. ‘It can feel that at the start of a portrait the person is apprehensive and I guess you just have to get them on board. It’s a creative process, but you have a technique and a process that you follow.’ For David, this process begins with drawing straight onto the canvas: ‘I might do some little thumbnail compositional mock-ups in my sketchbook, just to get my head around it. But I tend to draw with charcoal onto the canvas.’ However, it’s the in-person sittings – ‘I would hope for at least four sittings […] And if they had time, then, up to eight’ – through which his portraits develop. ‘At the heart of the picture is this kind of encounter. That sort of engagement that we had, that intimacy. I think that’s really important to me, that human connection.’

David will sometimes take photographs for reference but is reliant on in-person interactions and, crucially, time, to bring his oil paintings to life. We touch on the role of photography, which David feels is distinct to that of a painted portrait. There’s no hierarchy, he says, but feels the process of painting is more apparent in the final product. ‘It’s layered. If a camera creates one shot, then a painting becomes a thousand, kind of, glances of the artist’s eye […] it’s an amalgamation of everything put into one image. All these different moments are summarised in one picture […] It’s very slow, actually, for the modern world. It’s a really slow thing.’

There’s a sense when speaking to David that a painting is not only the sum of its parts – paintbrush, oils, canvas – but also the sum of our parts – the artist and the sitter. With the individuals as integral to the outcome as materials, it seems inevitable that traces of the human interaction are present in the work: a detail that catches the artist’s eye because of its unusual shape may become emphasised in the composition, the mood in the studio may sway the colour palette. ‘It should feel human. It should feel like an encounter between two people, whether that’s the painter and the sitter or the sitter and a viewer. That sort of reaching out should be there in some way.’

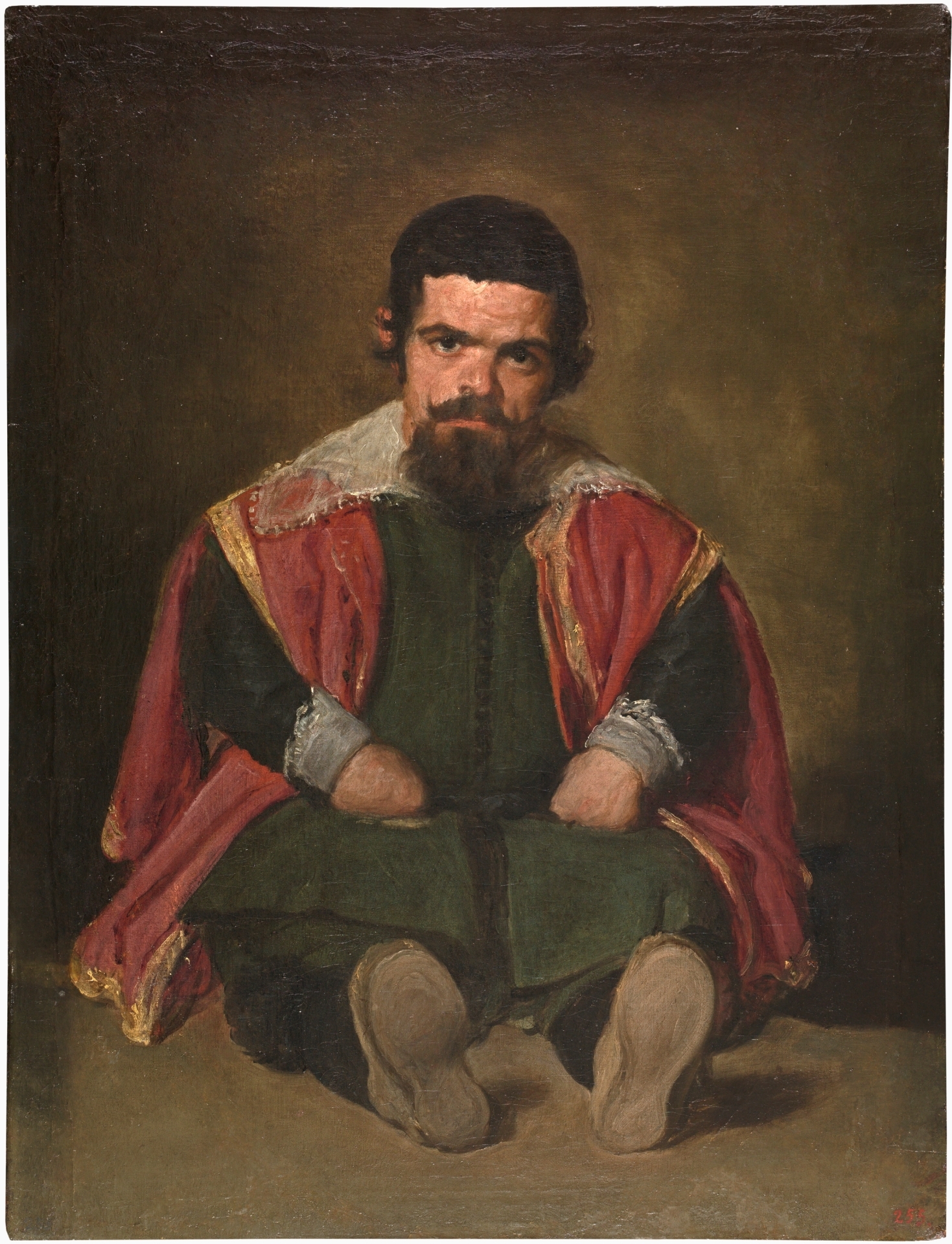

We discuss the historical portraits that have best succeeded in this. The paintings in which the sitter, like a compelling character in a novel, is depicted with such astute observations that the viewer cannot help but imagine them as real. One artwork immediately comes to David’s mind: Diego Velázquez’s 1644 portrait of Sebastián de Morra, a jester at the court of Philip IV of Spain. ‘He’s just sitting there. It’s very simple. There’s nothing in the background and it’s so arresting.’ Like so many portraits by the Spanish master, its success lies in exceeding its primary role – a faithful rendering of the person – to convey a lifelike, nuanced individual. ‘Those eyes looking out of that frame, it feels like it relates to all of us. The portrait could be of a universal human [...] There’s a kind of sadness and defiance. There’s all sorts you can read into those eyes.’ The simplicity of Velázquez’s composition, his focus on the individual and, perhaps most importantly, sense of empathy, are all stylistic and tonal qualities that chime with David’s own practice. Despite the distinctly historic garments – the red cape with fine gold trimming; the translucent, white-lace collar and cuffs – the portrait’s naturalistic style and unadorned backdrop enhance its relatability for contemporary viewers. As opposed to Velázquez’s famous group portrait, the enigmatic 'Las Meninas', which has soared through the historical canon in large part because the scene defies a straightforward reading, Sebastián de Morra's impact lies in the artist’s attentive portrayal of one sitter. Like all great portraits, it has captivated generations of viewers and withstood David’s most important test: time.

List of Images

1. David Caldwell RP in his Studio in Glasgow

2. David Caldwell RP, 'Girl with Orange Jumper', oil on linen, 180cm x140cm

3. David Caldwell RP, 'Portrait of Justin Currie', oil on linen, 180cm x 130cm

4. David Caldwell RP, 'Vanessa', oil on linen, 45cm x 65cm

5. Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez, 'The Buffoon El Primo', 1644, oil on canvas, 106.5cm x 82.5cm, P001202, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. All rights reserved.

Contact Us for a Portrait Commission

Martina Merelli, Fine Art Commissions Manager

+44 207 968 0963