Q&A with the Artists of [RE]Configured

Contemporary award-winning figurative artists Thomas Allen, Phoebe Boddy and Zara Matthews will show a selection of their most recent work in [RE]Configured, on show in the North Gallery from Wednesday 27 July until Saturday 6 August 2022. Through their three different styles and approaches, visitors will be able to enjoy a breadth of figurative painting. Keep reading for a Q&A with the featured artists, to learn more about their inspirations and what to expect from the exhibition.

Thomas Allen

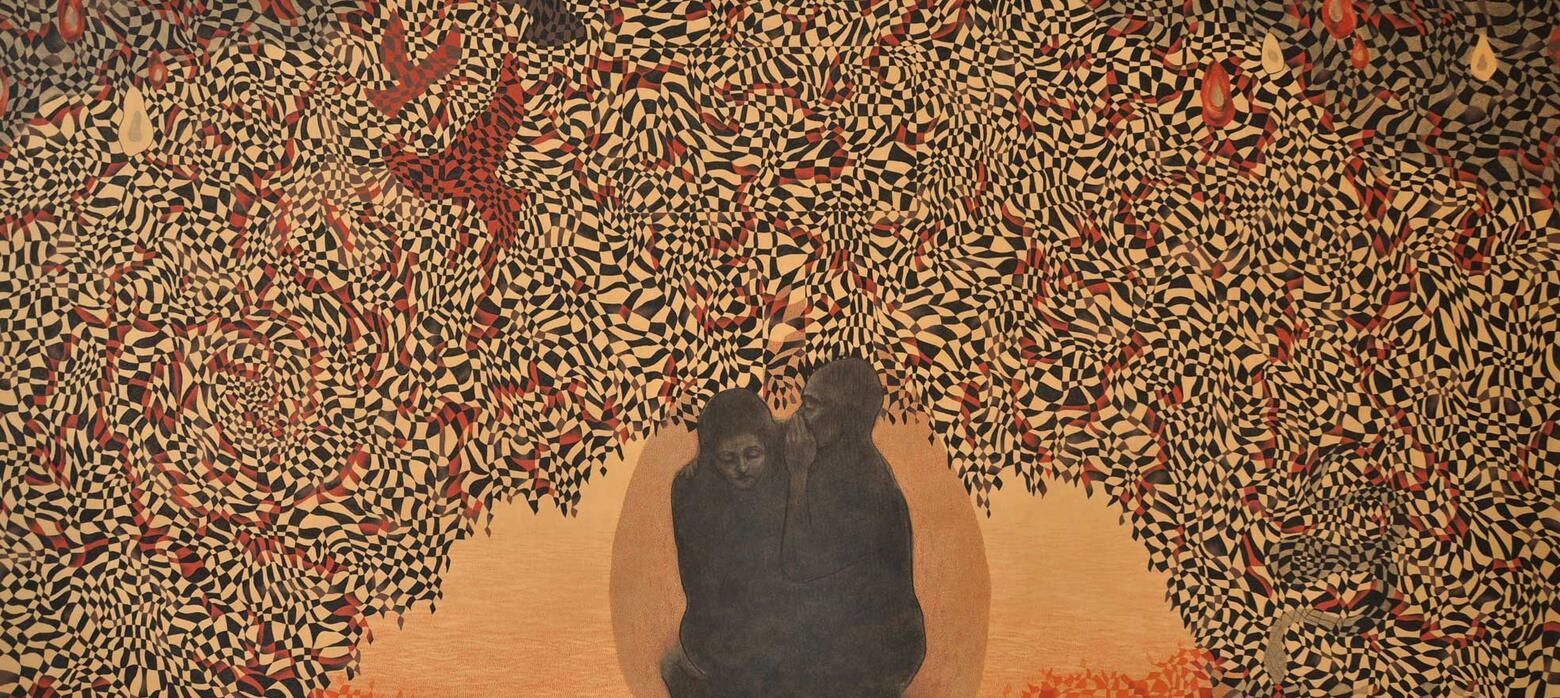

For this exhibition, Thomas Allen has created an array of works largely creating charcoal and sanguine works on paper. Some are immersive in scale, befitting the depth and breadth of the topics tackled, from online privacy to Christian mythology, romantic love to our relationship with the natural world. All are brought together through the artist’s signature dreamlike style.

Lucid Dreamer (diptych), Thomas Allen, 70 x 100 cm, £3,400

Q: Are you able to talk about your material choice - what draws you to working with charcoal and sanguine and how do you go about effectively using a limited colour palette?

I’d previously been creating pen and ink drawings. The fine-nibbled pens limited the scale of the work, so by moving to charcoal I was able to expand. Pen lines that were a hair’s breadth became charcoal lines several millimetres thick, and the surfaces I worked on were now measured in metres rather than centimetres.

The expansion was not just physical but also conceptual. I was developing a concept on Contemporary Cave Paintings for which I needed to fill entire walls with imagery, and charcoal and sanguine were a natural choice of materials given their prehistoric use. I came to enjoy working on a larger scale making more immersive pieces, and the creative process itself involves the body more fully as I’m moving around on my feet rather than sitting at a desk.

The more I work in a particular medium, I find it’s like language, it takes time before you start dreaming in a new language but then you come to interpret the world through it. Shifting into a different medium takes some effort and sacrifice though. Sacrifice because I have to let go of ideas and effort because I have to push myself to think in a different medium.

As for the limited colour palette of charcoal and sanguine, I find it quite liberating. You could pick up a piece of charcoal out of a firepit or a lump of chalk from a hillside and work with that - you aren’t encumbered by the need for turpentine with oil paints or zinc plates for etching, so in that sense, I like the idea of simplifying. There’s a directness of expression with charcoal and form and mark-making are brought to the foreground. That’s not to say I don’t also like to use other mediums though – watercolours, oils, pastels - they all open up different possibilities. In fact, I’ll even be showing some NFTs in this exhibition – a far cry from the humble charcoal stick!

Q: Within your work, you incorporate a lot of patterns and sequences which relate to the dream-like themes and your fascination with the unconscious. Are you able to talk about this relationship in more detail?

Our experience of the world constantly fluctuates between the figurative and the abstract. Take a tree for example: as a whole, it can be recognised as a tree but peer into the complexity of its foliage and it becomes abstract. This tension between the abstract and the figurative pervades our experience as we’re constantly channelling the tsunami of information from our environment into a comprehensive trickle. Humans are talented pattern finders giving us a great capacity for imagination. By distilling the busy world into simple forms we uncover hidden connections, extrapolate meaning and think abstractly.

This pattern-seeking tendency of ours has historically been used by psychoanalysts and the Surrealists to tap into the unconscious such as through Rorschach inkblot tests and through automatic drawing and writing. Interestingly, reaching further back in time to prehistory, it’s been observed in cave paintings that those nearer the mouth of the cave tend to be a series of dots and geometric shapes, while those in deeper chambers are figurative, and this progression mirrors the experience of sensory deprivation: when a person is put in a dark, silent room, after a while their brain generates imagery so that dots and grids appear in their mind’s eye, gradually morphing into geometric shapes and eventually into figurative imagery.

So perhaps this explains my heavy use of pattern, given that I’m interested in our internal landscapes, or ‘mindscapes’. It comes down to the very way we experience and make sense of the world.

Q: What can our visitors expect to see from your work in [RE]Configured and what have your inspirations been behind your new pieces?

For this exhibition, I’ve created a body of works executed mostly in charcoal and sanguine on paper. They range in size and in the topics they tackle – from online privacy to Christian mythology, romantic love to our relationship with the natural world. But the meanings they hold for me don’t really matter. I encourage visitors to dream before the images, to swim in the feelings they evoke or find their own meanings. And that can most effectively be done by experiencing the work physically. So I urge people to come along to the show!

Encrypted End-to-End, Thomas Allen, 150 x 270 cm, £8,500

You can see more of Thomas’ work at www.thomasallenart.wordpress.com

Phoebe Boddy

Phoebe Boddy’s most recent collection of paintings has been stimulated by how other artists have referenced food in their work and what messages they are trying to portray. She also draws inspiration from little sayings or bits of terminology referring to food that she finds entertaining. Her large-scale paintings are playful and often humorous, composed of energised brushstrokes and infused with a bold use of colour and form.

Two Pints of Lager (diptych), Phoebe Boddy, 170 x 260 cm, £6,800

Q: Your paintings incorporate very bold and energetic brush strokes, can you talk about your creative process and the physical energy that goes into your large-scale paintings?

My paintings usually begin when a very clear image pops into my head; this has often stemmed from something I’ve heard or seen that I have found inspiring or entertaining, and I have instantly created a composition to relay it. I really love creating large-scale pieces, I love to be completely engulfed by my paintings and I enjoy the process as when I paint I can’t see the whole surface, it is only when I step back that I can see what’s been happening!

Q: You say your collection of paintings in [RE]Configured have been stimulated by how other artists reference food. Who are your biggest artistic inspirations and what draws you to depicting food?

Sarah Lucas’ painting ‘Self Portrait with Fried Eggs’ inspired my initial painting in this collection – ‘Eggy Bread’. I am so drawn to her work because I really love how she uses food in a playful way, yet she highlights feminist themes & forces the viewer to consider derogatory perceptions of women. After being inspired by Sarah Lucas, I then went on to look at other artists such as Linda Nochlin, Claes Oldenburg and Salvador Dali.

Food is such an essential part of everybody’s life, whether you eat to live or live to eat, it’s a daily motive for all of us. This makes for a great subject matter as it can become something mundane, but the idea that everyone experiences food so differently is really exciting to me and allows for so many avenues of exploration. People are attaching memories to food and eating experiences all the time. I hope that when people ponder my artwork they are transported to these places.

Q: There is a lot of joy and humour in your work, are you always noting down the sayings and phrases you use and can you talk more about the relationship between your images and typography - do you see the written text as an extension of the painting?

I do see the text as an extension of my paintings, I love to see texts in paintings – when there is no text in them I am always looking to find a title. I like to connect the visual with words. My paintings will often start with funny quips, sayings or written words I have seen and heard, and because this is where it all started, I feel involving them within the painting makes sense. I also think text and the way that letters are written are beautiful. As my paintings are so bold and direct in their use of form and colour, the text I incorporate achieves this same instancy.

How d'ya like them Apples, Phoebe Boddy, 180 x 160 cm, £6,000

Visit www.phoebeboddy.com for more of Phoebe’s work.

Zara Matthews

In her practice, Zara Matthews works with photos, drawings, collected objects, mirrors and reflections. For this collection she has been experimenting with a process called Pentimenti, where paintings are altered, evidenced by traces of previous work. Using layered photographs and video stills of found objects, the works emerge from digital sketches before being developed into paintings. Through the Pentimenti process of incorporating underlying images, transparent forms and marks reference the objects’ aura, presence and residual memories.

The Poetry of Things, Zara Matthews, 115 x 170 cm, £13,200

Q: Objects we own, interact with, or discard, carry a lot of stories which is very evident in your work. What draws you to depicting these objects and are you able to talk more about the residual memories they carry?

I find objects that have been accidentally discarded or left behind the most interesting. Whether it has been thrown away or is on display in a museum doesn’t really matter - it’s the aesthetics of an object, such as a colour, intriguing shape or material that attracts me to it initially. An object’s isolation and vulnerability within its environment often enhances its aesthetics. The very act of drawing or photographing an object adds interest and fascination and when I look at them further they act as a visual trigger for my imagination, and the work becomes about the poetry of ‘things’. So the act of depiction brings other aspects into play, in the same way that a spectral image, enhanced colour or aura can hint at a history or presence.

Q: How do you find the objects you paint and do you set up the compositions or paint them as you find them?

It seems as though objects find me. Recently these have included stretchy fluorescent yellow netting used to protect fruit, an abandoned black cardboard coffee cup, a 2,700-year-old ivory vase from Assyria I saw in a museum, and some spoons and drinking glasses on a ledge in an artist’s studio I saw through a semi-opaque window. Today, whilst working on an idea for a new painting that has mostly dark objects, I left the studio, and then when I returned, I found a dark grey partially deflated balloon on the ground by the studio door. On an aesthetic level, its dead submarine colour and form seemed contrary to a party theme, and now it is joining other dark objects in a painting.

If I can take an object back to the studio or spend time making a drawing then I do. Otherwise, I take photos or draw from memory. Drawing or setting up a photo heightens my observations as shapes get simplified and I notice details which might ordinarily be overlooked. Sometimes I set up compositions and other times I combine or layer objects together digitally, but often it is a combination of both.

Q: The Pentimenti process you’ve used for the pieces you’ll be exhibiting in [RE]Configured is a really exciting way of working. What has drawn you to the process and can you describe the practicalities?

A pentimento means a change of mind. Pentimenti is a process of making things appear and disappear with corrections and alterations made by the artist as part of the creative process. In a way, Pentimenti is the art of erasure, leaving traces of an earlier image beneath a layer of paint, where the original image survives as a faint impression. Historically, artists took care to conceal the changes they had made which only became visible under infrared scans, such as with the blessing hands of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ or the hands in Jan van Eycks' ‘Arnolfini Marriage’. Painting allows you to change your mind and revealing these changes gives insight into the working process by showing what has gone before.