The Changing Face of Portraiture

/ Royal Society of Portrait Painters

Antidotes to Automation by Anna Godfrey

There are several stylistic similarities between the paintings of Miriam Escofet and those of Nathalie Nahai. Both artists produce hyperrealistic artworks with great care paid to the interplay of light and shade, of softness and solidity.

Miriam Escofet’s labyrinthine portraits depict sitters with gleaming, high-definition detail. A subtle overripening of reality tinged with fantasy. Take her painting of 'Professor Sir Mark Welland': the work is a meticulous balancing of repeated patterns, precisely interlocking like Russian dolls within the painting’s considered structure. The intricate Catherine-wheel glinting on the mosaic floor, for example, is a nod to Professor Welland’s role as Master of St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, but also to Artemisia Gentileschi’s 'Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria' (about 1615–17) which can be glimpsed in the upper-right corner. This is a painting laden with clues, in which connections spark freely between facets of the sitter’s identity and that of the artist’s.

Nathalie Nahai’s portraiture is also executed in an alluring hyperrealist style but with a greater leaning towards simplicity and, perhaps, stillness. In 'Light in the Well of Shadows', the viewer is lured by an image of a striking young woman positioned in profile against a featureless black background. The woman’s hand is gently raised and, suspended inches above it, floats a tiny ball of light – an intriguing scene which draws us, the viewer, like a moth towards the small light. The sitter’s dewy skin glows against the seemingly cavernous darkness. Emptied of compositional clues, the piece adopts a philosophical tone reflective of both the sitter’s gentle curiosity and, perhaps, Nathalie’s own probing mind (alongside her visual art, Nathalie is an author, musician and keynote speaker whose work focuses on AI, human behaviour and ethics).

We meet to discuss their work and what they feel the future of portraiture may hold. Like the other artists interviewed in this series, the individuality of their artistic process is apparent. Miriam highlights her early training in three-dimensional design and an enduring interest in ‘the idea of how an object sits in space and the construction of this on a two-dimensional surface’. There is a sculptural, almost mathematical underpinning to the way in which Miriam builds compositions. Such planning requires her to take numerous photographs alongside live sittings before she develops the work through time and solitude: ‘I don’t enjoy having the sitter in front of me for the key bits of the progression of the work – the alchemical bits’. She requires space for her imagination to play with what she perceives, suffusing the work with the ‘very subtle surreal edge’ that elevates her compositions. Nathalie’s approach is more sudden: ‘I have a creative visualisation practice […] a kind of meditative practice. And in this practice, sometimes there’ll be images that come fully formed to my mind. Then I just feel compelled to paint.’ This feeling of an image coalescing resonates with Miriam: ‘I call it when the painting comes alive […] you will recognise it and that’s when you think, oh yes, that’s when something’s happening. It goes beyond craft.’

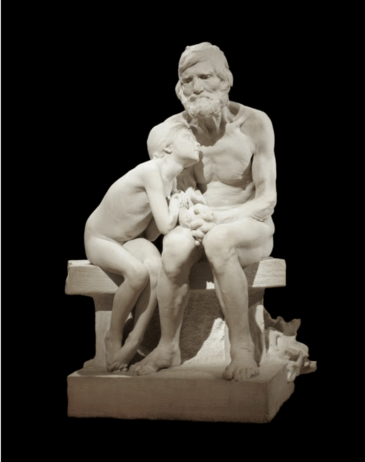

Each, it seems, is compelled not only to record an arresting image but to imbue a real scene – in the case of portraiture, the likeness of the sitter – with the workings of their imagination. This is coupled with the desire to capture and pay homage to human connection. As Nathalie says, ‘I think artists spend years dedicating their attention to others, that alchemical reaction when two bodies are in a space together […] I think it’s particularly precious’. Miriam echoes the sentiment: ‘it’s impossible to be a great portrait painter without having empathy’. The historical artworks they most admire attest to this. Miriam cites Hans Holbein as a key influence: ‘what’s so brilliant about Holbein as a portraitist is that when you stand in front of a Holbein portrait, you feel you’re in the presence of an individual. You can read the character in that face [...] his ability of observation is incredible.’ Whereas Nathalie cites the 1892 sculpture 'The First Cold' by the Spaniard Miguel Blay which, similarly, captivates because of the attention the artist paid to the individuality of his sitters. ‘It’s an old man, perhaps a grandfather, with a young child. And you can see the crepiness of the skin and this body that’s lived life. The tender form of the child is bent over towards him, and you imagine the warmth between them as the cold surrounds them.’ The impact of both Blay’s and Holbein’s work derives from the connection they establish between viewer and sitter. ‘That sense’ – Nathalie says – ‘of being in front of someone and knowing what it might feel like to fall into the body of the little girl or fall into the body of the old man.’ Like beloved characters in a novel whose quirks encourage us to imagine them as real, with a painted portrait: ‘the more personal you get, the more universal it becomes. The more generic you are, the more washed out it is.’

This emphasis on the importance of a person’s individuality brings us to the topic of technology. Although both are reliant on some digital tools to create their work – ‘As well as drawing from life during sittings, I take a lot of good reference photos and then edit those on my computer’ says Miriam – they are sceptical of the growing role of AI. ‘It ends up creating perfect but generic images’, argues Miriam, ‘I think we’re going to become swamped by AI imagery in the art world, and, well, there is already a market for that. I think it will have an impact, then I think there’ll be an aesthetic rebellion against it [...] what we might find is that artists try to find another language that signifies, I’m not a machine, I’m a human, and this is how a human paints. It might change our language as artists down the line.’ She raises a pertinent question: in a landscape saturated with imagery created through artificial means, might the rarity of the artist’s hand hold even greater value?

Nathalie mentions a friend, Carl de Jager, who’s a painter and ex-developer: ‘he plays around a lot with Midjourney to generate images and he’s trained an AI with his own artwork to create images in a particular style. I think that’s a really interesting experiment because it’s a sense of understanding that if you put certain information in, you can edit what comes out. But there’s a big distinction between creativity and editing.’ This harks back, again, to the importance of process and, when viewed from that angle, the value of AI becomes muddied. ‘When it comes to using AI’, Nathalie remarks, ‘while the prompt can be creative, the idea that you might have a way to translate some vision in your mind into language, which then gets translated into an image, which is based on the historical output of humanity that is available for that AI to have been trained upon…It’s difficult.’

The question of the importance of originality to artistic worth is one argument that has been levelled against AI. However, there is also a subtler concern of which AI is, arguably, just the latest manifestation: the creeping pressure for people to optimise every moment of their time. As Nathalie states: ‘I think that art and the process of creativity are antidotes to automation. Automation is about reproducibility, optimisation, efficiency, productivity [...] That in itself gives us what I think we need increasingly to get out of: this really frantic, anxious state where we feel frozen by the speed at which things are going.’ It’s the double-edged sword of contemporary Western life. Although the affordability and prevalence of digital technology allows for a hyperconvenient, tailored servicing of our needs, the extent of its integration breeds dependency and an inability to switch off. In this way, portrait painters might exemplify an alternative approach to time and a different definition of productivity. Making art reinstates, as Nathalie articulates, ‘the joy of being in real time and real space, which is what the digital world takes you out of.’ Miriam agrees: ‘I think it’s all to do with this idea of the shortcut [...] That culture of convenience is so embedded’ and from this – Nathalie adds – ‘It may mean that in the future we’re going to seek out the kind of art that gives us other ways forward, that creates these kind of lifelines’.

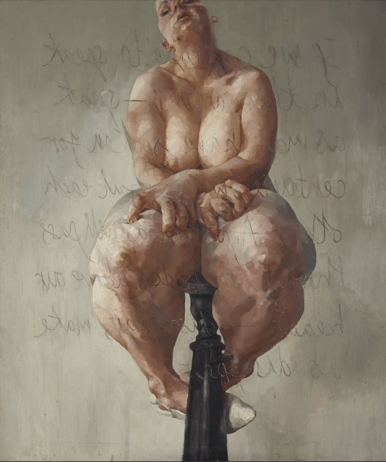

When we discuss the evolving state of how art is made, it’s not simply ‘machine’ that ‘man’ is compared to. It’s also the rise of women painters. Miriam recalls being at art school in the ‘90s: ‘it was dominated by the big male beasts. All the big-name artists were male artists and it didn’t mean that I didn't like them – I thought some of them were marvellous. But as a woman, it was very hard to identify with that or to see yourself in that role.’ Now, she feels, there is greater balance. Not only in the number of women artists but also in a broadening of the type of art associated with women: ‘like Jenny Saville who’s making these visceral, fleshy, kind of bloody images. I love her work [...] I think she’s a great role model for female artists. It’s bold and it takes up space’. Although representation within the art world is by no means a straightforward success story, there is a pattern of positive change over the previous 30 years that they hope continues over the coming decades. To increasingly expand – as Miriam puts it – ‘every kind of representation in the art world’.

We finish our conversation on the future of portraiture with a reflective note: taking a moment to acknowledge that, in looking ahead, we are implicitly recognising what’s come before. As Miriam aptly concludes: ‘however modern and inventive, we all draw from the past to do what we do. There’s a lineage to everything’.

List of Images

1. Miriam Escofet RP with the portrait of her father titled 'What will survive us...', mixed media on linen over panel, 90cm x 80cm

2. Miriam Escofet RP, 'Professor Sir Mark Welland, Master of St Catherine’s College Cambridge', oil on linen over panel, 120cm x 90cm

3. Nathalie Nahai, 'Light in the Well of Shadows', oil on canvas, 50cm x 67cm

4. Miquel Blay, 'The First Cold', sculpture, 980cm x 1367cm x 718cm, Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya

5. Miriam Escofet RP in her studio in London

6. Nathalie Nahai painting a portrait

7. Jenny Saville, 'Propped', oil on canvas, 213.4cm x 182.9cm, Sotheby's, The History of Now: The Collection of David Teiger, Lot 6

Contact Us for a Portrait Commission

Martina Merelli, Fine Art Commissions Manager

+44 207 968 0963